Of good schools and level fields

New rules for primary school registration aim to improve access and inclusivity for popular Singapore schools, but may end up sealing current inequalities instead.

Nov 12, 2021

AS her daughter turns 5 next year, Angela (not her real name) could soon be looking for a new home. She is keen for her daughter to enrol at her alma mater, a popular school along Dunearn Road. But with revised rules for Primary 1 registration slated to kick in from next year, Angela is worried that her daughter may be squeezed out of a spot.

The Ministry of Education (MOE) in September set in motion changes that effectively give greater priority to those living close to the school, at the expense of those with other links to the school, such as alumni and clan associations.

The ministry also revised the methodology for calculating the distance between home and school for all primary schools, resulting in a slightly larger coverage of homes considered to be within 1km and 2km of the school of choice. This will result in slightly over 10 per cent more homes added to the list of those who are within 1km and 2km of primary schools.

Following the announcement, Angela says the school’s alumni association held a dialogue session with parents eager to send their children to the alma mater. It had run a simulation of the registration exercise, based on factors such as the size of the cohort, and estimated that there would likely be sufficient spaces for children of school alumni without having to ballot for a spot.

Still, Angela says she plans to buy a house within 2km from the school – just in case.

“I try not to take chances if possible,” Angela says, adding that living near the school would also make it more convenient to ferry her daughter to and from school.

As a real estate agent, Angela says she has not yet noticed any significant uptick in prices for properties near the popular schools, which typically already command a premium in the market. But she believes the increase in prices could be more prominent over the coming months, especially from early next year ahead of the next school registration exercise.

According to the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), prices of private residential properties increased by 1.1 per cent in Q3 2021, up from the 0.8 per cent increase in the previous quarter. This was driven by landed properties, which saw values climb 2.6 per cent during the quarter, compared with the 0.3 per cent decline in the previous 3-month period. Meanwhile, prices of non-landed properties increased by 0.7 per cent.

Finer grained data shows distinct trends in interest and values of properties near popular schools.

Looking at resale prices of private apartments and Housing Development Board (HDB) flats between 2019 and 2021, OrangeTee & Tie senior vice-president of research and analytics Christine Sun found that on average, the median prices of resale homes within 1km of some popular primary schools had outperformed that of others in the same district.

For example, data compiled by OrangeTee showed that the median price of resale non-landed private homes within 1km from Anglo-Chinese School (Junior) at Winstedt Road off Bukit Timah climbed 6.2 per cent to S$1,974 per square foot (psf) in the 7-month period between January and July 2021, from S$1,859 psf in the corresponding period 2 years ago in 2019. In comparison, the median prices of resale non-landed private homes in the wider District 9 that the school is located in had dipped 4.5 per cent to S$2,053 psf this year, from S$2,149 psf in 2019.

Near St Hilda’s Primary School in Tampines, median resale prices for condominiums within 1km from the school jumped 32.8 per cent to S$1,130 psf compared to 2 years ago. In the wider District 18, median resale prices edged up by just 2.6 per cent to S$1,018 psf over the same period. Similarly, the median price of resale HDB flats within 1km of the school rose 15.5 per cent from Jan-Jul 2019 to Jan-Jul 2021, slightly faster than the district median price increment of 12.8 per cent over the same period, Sun says.

HDB resale flats near Nan Hua Primary School in Clementi saw the biggest percentage point difference between the 1km circle and those in the wider district. The median price of HDB units within 1km from the school jumped 45.4 per cent year-on-year to S$727,000 in the first 7 months of 2021, against the median resale price of HDB units in District 21 that rose 21 per cent to S$472,000.

The median HDB resale price within 1km from Pei Hwa Presbyterian Primary School in the Bukit Timah area also climbed 16 per cent to S$891,000, compared to a 2 per cent dip in the median price for resale HDB flats in District 10 to S$702,900.

Is it the school?

“It is quite common for developers to market projects near popular schools at a price premium of up to 15 per cent,” Sun adds. However, she notes that there are other factors at play, such as the potential for future development.

Ong Teck Hui, senior director of research and consultancy at JLL Singapore, agrees that besides schools, other attributes such as proximity to MRT stations and amenities such as shopping, food and beverage (F&B) and recreational facilities, exert an influence on prices of homes.

“The district price changes would also be influenced by new launches – or the lack of it – as new project sales could lift median prices,” Ong says. In addition, “the age of a project affects its value and older projects command lower values than newer ones, ceteris paribus,” he says.

The way ERA Realty head of research and consultancy Nicholas Mak describes it, the proximity to popular schools is a “good-to-have” factor, but not the only price driver.

“Not every home buyer cares for the presence of a popular primary school in a neighbourhood,” Mak says. “Some buyers, such as those without school-going children, would consider other factors concerning the property to be more important than the presence of the school … And this group of buyers may be in the majority.”

He also believes that, in some cases, proximity to popular schools may be taken for granted over time, and thus have little influence on property prices.

“It is only when the school moved away from the location (that) there could be a negative effect on property prices there,” Mak says.

On the flipside, this could mean that properties that suddenly find themselves deemed to be close to schools could see a positive effect. Already, some property agents have noted a visible hike in interest in properties that have sneaked into the 1km radius from popular primary schools following the revised methodology on proximity.

Alex Goh, associate executive director at OrangeTee & Tie, points out some examples of private property projects that have “definitely” scored an increase in interest because of this. For instance, he says, the upcoming Leedon Green project along Farrer Road now falls within 1km from the highly regarded Nanyang Primary School.

“We noticed a slight spike in sales in September, which is likely due to agents using this news to convert fence-sitting prospects,” says Goh. He says 37 units at Leedon Green were sold at an average of S$2,717 per square foot (psf) in September – when MOE announced the changes – compared to the 30 units sold at an average of S$2,648 psf in the previous month.

At The Woodleigh Residences, 19 units sold in September, up from 16 in the previous month, at average transacted psf prices of S$2,128 in September, from S$2,118 psf in August. The Woodleigh Residences at Bidadari is now within 1km from the primary section of Maris Stella High School. Interestingly, some blocks within the project will now also be considered within 1km from St Andrew’s Junior School, while others fall outside of this prized 1km radius.

At the upcoming Verdale condo too, along Jalan Jurong Kechil, just outside Bukit Timah, only certain blocks within the project are now 1km from Pei Hwa Presbyterian Primary School.

“We have already seen a premium for projects within 1km from popular schools, and in fact, premiums for selected blocks within a project,” Goh says. “Emotionally, it is a powerful trigger as buyers buy on emotion.”

Better access to schools – for who?

MOE said the changes in P1 registration rules were made to ensure more children have access to schools near where they live, regardless of whether they have any advantage in the entry process.

Commenting on the proposed changes, Education Minister Chan Chun Sing noted that the number of pupils who can access a school near their home without affiliation has declined in recent years. He added that the latest revision would help ensure that schools remain accessible, open and inclusive.

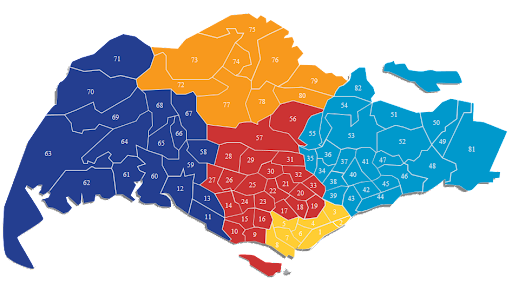

Yet some of the most popular primary schools, such as Nanyang Primary School, Raffles Girls’ Primary School and Anglo-Chinese School (Primary), are concentrated around the affluent neighbourhoods near Bukit Timah.

The popularity of schools such as Ai Tong School and Catholic High School (Primary) is also seen to have driven up the prices of property around Bishan. A 5-room HDB flat in Bishan, just across the road from Catholic High School, was sold for an all-time record of S$1.36 million in October.

While well-intentioned, giving priority to proximity potentially runs the risk of further widening the gap between the haves and have-nots.

Property prices around the so-called “elite schools” will inevitably continue to rise as well-to-do families fork out premiums for a higher chance of entering these popular schools. The less affluent will have to make do.

Tan Ern Ser, associate professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore, believes the revised rules could translate into an “unequal probability” of getting into a choice primary school if the affluent are more likely to qualify to ballot for a place for their children.

“However, unless we have the data to do a before-and-after comparison between previous schemes and the new scheme, we would not be able to argue definitively that the new scheme has paradoxically increased inequality of access,” Prof Tan says.

“In my view, if we are aiming to have a totally level playing field, the gold standard to adopt is to have choice schools in every town, or where every school is deemed to be a good school and perceived by parents to be indeed so. This would eradicate the advantage of proximity,” he adds.

Beyond grades and ‘good schools’

To be sure, uprooting the family for the sake of a better future for the children – perceived or otherwise – is nothing new.

A Chinese phrase, meng mu san qian, is derived from the story from ancient China of how the mother of Mencius (Meng Zi) moved 3 times to find the right place for his upbringing. They finally settled down near a school, where the young boy saw people treating each other politely and heard the sound of reading all day long. It must have worked, as Mencius turned out to be a famous Chinese philosopher, who is thought to be the most famous Confucian after Confucius himself.

Luckily for Mencius and his mother, they did not have to grapple with additional buyer’s stamp duties, total debt servicing ratios, or eye-watering per square foot prices in the choice locations. But, close to 2,400 years later, it seems little has changed when it comes to parents hoping to give their children a headstart in life.

For its part, MOE has embarked on initiatives to play down emphasis on grades. In 2012, the ministry discontinued its practice of revealing the names of the top-scoring pupils in all national examinations. A year later, it also stopped including the highest and lowest aggregate scores in the results slips of students in the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE).

While there is no official ranking of schools, several websites publish their own rankings. Some are based on crowdsourced information on PSLE scores, which were submitted by parents.

Even before this, MOE had also introduced the Direct School Admission (DSA) scheme in 2004, which was aimed at cultivating a flexible and broad-based education system in Singapore that looked beyond grades. Before taking the PSLE, students can apply to educational institutions such as secondary schools and junior colleges based on both their academic as well as non-academic talents and achievements, including sports, arts, and leadership. The scheme also includes an interview process.

While the intention was well-meaning, the DSA scheme may have backfired and sparked a full-blown arms race, as parents enrol their children in enrichment classes to increase their chances of getting into the top schools via the scheme – on top of continuing their tuition classes to keep their grades up, in case they fail to be accepted.

This year, some 12,100 Primary 6 students applied under the DSA scheme to secure their position in their secondary schools of choice, up from 11,900 applicants a year ago. Only around 3,600, or 1 in 3 applicants in 2020, were accepted under the scheme.

And applications continue to be skewed towards the “brand name” schools. For example, Raffles Institution (RI), Singapore’s oldest school which counts 4 past presidents and 2 former prime ministers among its alumni, is reported to have received an “overwhelming” number of applications this year.

The school, which typically has about 30 per cent of its Secondary 1 places taken up by DSA applicants, said there were about 13 applicants for each spot this year.

The competition for limited DSA spots has driven business for some enrichment centres. Some, such as Speech Academy Asia, help students with their public speaking skills, which is one of the DSA categories. The enrichment centre also trains its students to ace the interview, giving them tips to answer over 80 questions that are most likely to be asked by interviewers.

The ability to confidently answer these questions during the interviews, says Speech Academy Asia’s director and co-founder Kelvin Tan, is “half the battle won”.

“In the last 3 to 4 years, we have seen an increase in the number of enquiries for our DSA interview courses,” Tan says. The average cost for the courses are around S$65 per session.

According to figures from the household expenditure survey, which is conducted once every five years by the Singapore Department of Statistics, average household spending on tuition has risen from S$79.90 per month in 2012/2013 to S$88.40 per month in 2017/2018.

It is not unusual for affluent families with several school-going children to rack up bills of up to thousands a month for tuition and other enrichment classes.

But, for parents and their children, the costs could be much higher than purely monetary.

“That the education system here produces high stress levels for both parents and children is not new. Most parents want their children to do well in life, and academic achievement is often seen as a proxy to that end,” says Alicia Boo, principal counsellor at Focus on the Family Singapore.

She cites an online survey the group conducted in September last year with over 1,050 school children aged between 10 and 15. Surprisingly – or perhaps not – the students were found to be more worried about their exams than the Covid-19 situation in Singapore.

“While it is common for examinations to induce short-term stress, chronic stress can lead to other forms of mental health issues such as clinical anxiety disorders, which if left unchecked, may require professional intervention,” Boo adds.

A mother of 4, the eldest of whom is taking his PSLE next year, Boo says parents should tune in to their children’s psychological and emotional needs. She adds that parents play an important role in building psychological resilience in their children for stressful situations.

At a smart parenting webinar organised by The Straits Times on Oct 30, RI principal Frederick Yeo said that gunning for a top school based on its academic prestige without considering how the child will take to the pace of learning may do more harm than good.

Noting that parents should talk to their children about their choice of school, he added: “It must be a school that he wants to go to; it can’t be a school that you want him to go to.”

NUS’s Prof Tan believes that revisions to P1 registration rules and initiatives such as the DSA scheme could be a step in the right direction. But while the heart is in the right place, he adds that the outcome may turn out otherwise.

“To get it right, we would need to tweak the criteria over time and use quality data to determine whether the system is becoming fairer. But constantly tweaking the criteria may have unintended consequences, and could be rather unsettling for parents and students,” Prof Tan says.

“With the world of work changing rapidly and the ‘multiple pathways to success’ a realistic target, the playing field could in time correct itself, with minimal tweaking,” he adds. “The best hope is to aim to have ‘every school a good school’.”

For now, however, parents such as Angela will have to continue to do whatever they can to increase the chances for their children to get into the more popular schools.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote